Barnaby Griswold has never been much of an athlete, or even very sportsmanlike; he tends to cheat when the match is on the line. He’s not much of a fighter either, more likely to throw a rock than an honest punch.

Barnaby Griswold has never been much of an athlete, or even very sportsmanlike; he tends to cheat when the match is on the line. He’s not much of a fighter either, more likely to throw a rock than an honest punch.

His father had hoped Barnaby might lead a life of dim propriety. But instead Barnaby has grown into his father’s horror: a great melon of impropriety, a fluffmeister, an investments player with unbelievably priceless instincts for the next deal.

Then he loses everything. Not just his wife and daughters. Not just his livelihood and connections and lunches at La Côte. Barnaby, without a nickel, is banished even from his boyhood summer home, the very last roof over his head.

Now, divorced, deserted, flat broke, Barnaby has to find a way to repair his life.

Can a fool–a clumsy, self-absorbed, insensitive, money-driven fool–become a hero, the kind of hero that makes us stand up and cheer? In a word, yes.

This is a funny, irresistible, resonant novel that, in Andre Dubus’s words, “brims with love.”

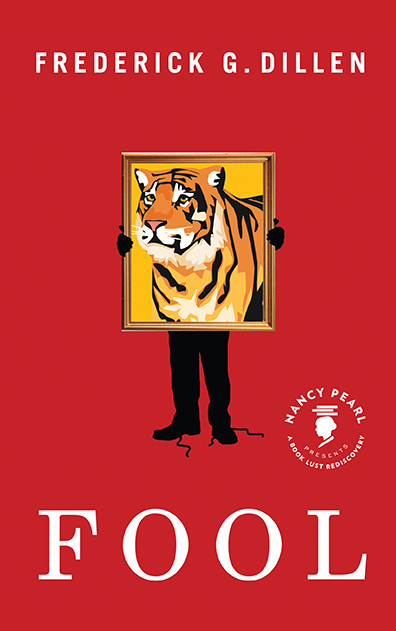

A Nancy Pearl Book Lust re-discovery

“Frederick Dillen writes with the excitement and curiosity of a child, and the wisdom and talent of a master. Fool is romantic, funny, sad, sometimes violent, and absolutely serious.” – Andre Dubus

“Fool is about masculinity, the likelihood of failing to achieve it and the possibility of redeeming it. The moving but unsentimental narrative and Dillen’s happily offbeat prose add a surprising twist to Barnaby’s redemption.” – New York Times Book Review

“As compelling as a romping game of tennis.” —Booklist

“[An] assured and sophisticated novel.” —Publishers Weekly

“Dillen’s prose is astonishing.” —Library Journal

Barnaby Griswold loafed and drank his way through good schools, but those were the days, God bless them, when the world made room for boys from families with the right balance of propriety and financial resource. Not that Barnaby didn’t take any lessons whatever from his education, but the real work of his youth had been to learn once and for all that he was intelligent only to the near side of cunning and that the fundamental truth of his life lay in foolishness. Books and study and logic and meditation were all fine for other people and for respectable decoration, but Barnaby was a fool no matter what his father had hoped and no matter how Barnaby had tried, briefly, to turn out otherwise, no matter how Barnaby continued occasionally pretending for his father whose last words to Barnaby were, “For Christ sake don’t become a fluffmeister.”

Those words reverberated as intended, but they were too late. The words that took precedence were “Know thyself,” words uttered, for all Barnaby knew, by one of his own ancestors. Barnaby was a fool, and he had learned it early. What was more, and more important, he had learned that the world reserved an agreeable place for fools who were prepared to stand up and claim their entitlement. He thought of that entitlement as a happy welfare with better neighborhoods, fun really. He had made his living as a fluffmeister, and it had been a good living. More and more, in fact, Barnaby wondered if his father had objected to his career not because of despicable reflection on any individual who chose to labor in the vineyards of fluff, but because the work paid well enough to suggest a world and life that were out of kilter. Barnaby’s father, who abhorred disorder and secretly distrusted life, insisted that fundamentally the world and life were good and right, insisted that it behove (behooved?) every decent man, gentleman or no, to insist likewise. Barnaby, on the other hand, who enjoyed things, knew there was much to be had in celebrating a deal, in New Jersey say, even a terrible deal, with appalling new friends and one of those green-and-eggplant sunsets.