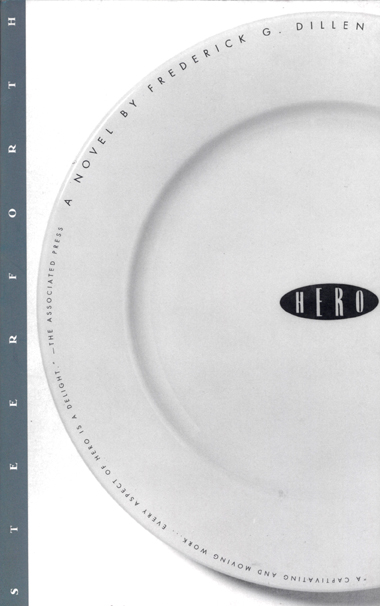

In a New York City steakhouse, with its high-ceilinged dining room, linen-covered tables, and its filthy, sweaty kitchens, an aging career waiter–jokingly nicknamed “Hero”–moves with numbed silence through his heavy litany of service. Once a successful college graduate but now a down-and-out loner whose alcoholic past haunts him, Hero must risk an old man’s precarious all to win honor in his restaurant world.

In a New York City steakhouse, with its high-ceilinged dining room, linen-covered tables, and its filthy, sweaty kitchens, an aging career waiter–jokingly nicknamed “Hero”–moves with numbed silence through his heavy litany of service. Once a successful college graduate but now a down-and-out loner whose alcoholic past haunts him, Hero must risk an old man’s precarious all to win honor in his restaurant world.

“A captivating and moving work… every aspect of Hero is a delight.” —The Associated Press

“Hero stands out for its intensity, for the resolute purity of its concentration and focus, and for its powerful, unflinching (and often wildly funny) vision of the raggedy rainbow coalition that is contemporary urban America. Hero is an experience real enough to become a memory. Dillen is a writer of great gifts, accomplishment, and promise.” –George Garrett, in his citation of Hero as the winner of the Dictionary of Literary Biography Award for 1994’s Most Distinguished First Novel

“Good things sometimes come in small packages, but it is not often that something this good comes in a package so slim and unassuming… the conclusion arrives like a sudden left hook from a crafty, overpowering heavyweight boxer… this novel is astonishing.” —Kansas City Star

“Fine, wonderfully short and tersely written . . . Completely engrossing for anyone who has toughed out time in the brass-knuckle world of restaurants.” –Katherine Powers, Boston Globe

“This brilliant short novel comes to a close, leaving readers with a silence that holds a hint of a smile.” —New Orleans Times-Picayune

“Fast, funny, and full of hope.” —Santa Fe New Mexican

“Not just poignant and charming but impressively realized as well.” – Times Literary Supplement

The first day in his new steakhouse he trailed another waiter to learn the service, and as he followed the waiter up the stairs from the basement kitchen, the waiter stumbled and upset a shouldered tray. Pops, or Dad, or whoever he would become, put a hand up and balanced the tray for the waiter. A third waiter saw it happen, and called out, “The new guy is a hero. Hero, listen, I want you to follow me from now on and catch my trays.”

The steakhouse was in mid-town Manhattan and was expensive, and on Sundays there was no business. Hero was the new man so he got the lousy shifts, and on one Sunday night the barman brought in a television with a screen the size of someone’s hand. It was October and the World Series, and Hero looked at it from across and behind the barman. If any of the other waiters had wanted to look at it, Hero would have gone without a thought back to his station or to sit in the kitchen, but the other waiters were foreign or were gay and didn’t look at baseball.

On the screen the third basemen punched his glove, and had a chew of tobacco the size of a golf ball in the right side of his mouth, and squirted spit again and again at the dirt. The barman kept the sound low enough that Hero did not have to hear the commentators talk, but the camera and the little screen looked at the third baseman, and Hero looked at the third baseman. And because even the World Series held no more interest than any other program for Hero, in another moment Hero would have drifted away.

There was a high foul ball, however, and the third baseman ran full speed at the dugout which fell in four, sharp, concrete steps to the line of the third basemen’s own teammates. At the last moment, the third baseman dropped to the seat of his pants and slid full force over the edge of the concrete steps, and, with the chew squeezed in the side of his face, watched the foul ball down into his glove, and then was hurtling among his teammates who tried to catch him and tried to keep his head from breaking open as it whipped back onto the concrete. The third baseman’s arms flailed from his washboard rush down the steps, and as he finished in a heap among the feet and the crouched uniforms of his teammates, the ball popped carelessly free. Up out of the heap, the third basemen stood slowly. His hat was off. His chew was in place. His teammates and coaches touched at him and asked at him and he nodded absently and reached down and picked up his hat and put that on and looked out to the field, shook his head slightly, climbed up two of the dugout steps, and was plainly not a boy with rubber limbs but a grown man who hurt. He stepped up the last two steps of the dugout and jogged out to his position at third base and punched his glove and spat and bent to give his concentration at the batter who readied for the next pitch.

“Hero.” There was a party of two at the desk. The maître d’ and the floor manager were downstairs in the office looking at a real television, and the old Iranian, the waiter who had taken the desk, summoned Hero. Hero now would have stayed to see more of the game, but it would never have occurred to him to say so, and he stood away from the bar.

“No,” the Bolivian said. “Hero doesn’t want a deuce. Hero’s American. He’s watching the World Series. Hero’s rooting for the Americans in the championship of the world only Americans play. Give the deuce to a foreigner, or one of the girls.”

“You think South Americans don’t play baseball?” the Iranian said. “You think the Caribbeans don’t play baseball? What’s the matter with you? Bolivian.”

“Don’t talk to me about South America, Camel Driver.”

“No wonder you can’t run your country. You can’t even read your own sports pages. You don’t know what happens in your own village.”

“Don’t talk to me about my country, Ayatollah.”

The Polack came at them, saying, “Listen to the Ayatollah. He knows baseball. He is going to start his own Iranian team and beat the American pigs.”

“Shut up, Polack. I’m talking to the Bolivian mother now. When I am done with him then I will tell you about what a piece of dung is your homeland. Solidarity, I spit on it.”

The Bolivian called loudly, “Ayatollah and the Polack. Khomeini and Martina.”

“You think I am going to listen to you?” the Polack said to the Iranian. “Old man? You come from the desert, you wipe with your fingers, you cook with camel shit. I am civilized.”

“What? Nobody reads in your village either? No schools? No history? I’ll tell you. Everybody pisses in Poland’s pot, from Ghengis Khan to Breshnev. Ignorant Polack. What do you know about civilization? I’ll tell…”

The deuce was in and one of the gays had taken it, and on television now the third baseman was sitting on the bench in this dugout, laughing with the guy beside him. The third baseman took off his hat and felt the back of his head and then bent his head and offered it to the next guy who touched it and laughed. A couple of the other guys reached over to feel the back of his head, and then the third baseman looked up at them and laughed again, and they laughed with him. He had a good face. When he laughed, he laughed.

“You’re a fan, Hero. I didn’t know you were a fan. I watch the Series here in Manhattan and I feel like I’m watching it in Sri Lanka or something, you know what I mean?” The bartender said that, and Hero stood back a step from the bar. He put a hand in his pocket to touch his keys.

When he was up, the third baseman only topped a grounder that rolled under the pitcher’s glove. Still there was no play, and he was on with a single.

“Good hustle,” the barman said.

Hero was no fan, and no athlete. That he watched at all was as odd and passing as anger. But his next time up the third baseman hit a double and drove in two runs, and Hero slapped his hand on the bar as the third baseman hit the dirt off his pants and worked his chew and spat and took his lead.

His last up, he lined a single and drove in the winning run. It was not the last game of the Series, but it was a Series game just the same, and he’d on it, and when he ran off the field with his teammates he lost all his concentration and was a boy with all the rest of his team, all them delighted in a bunch. In front of the camera, inside the clubhouse, he laughed out and shouted in a whoop over at someone outside the picture, and then turned and pointed down the clubhouse over the heads of his teammates and laughed and whooped again.

“Hey, Polack,” the Bolivian called. “Hey, Khomeini. Look at the Hero. The Americans must have lost.”

The announcer was calling him back, pointing after the third baseman and waving him back.

“Hero is crying.”

He was not sobbing. Not tears running down his face.

“The Camel Drivers beat the Americans in the World Series.”

He thought to go into the kitchen. He wiped his face and made his invisible smile. He knew it was best just to go away, yet he waited to see if the third baseman would come back for the announcer.

“Leave him alone,” the Iranian said. “Ignorant Bolivian.”

“It was a Polack National Team that wins,” the Polack shouted. “Iranians throw like girls. Everybody sees that from the embassy.”

“You think we didn’t beat the Americans, Polack? Ask Carter. Who did Solidarity ever beat?”

The third baseman stepped back up onto the platform with the announcer and, grinning, chew still deforming his plain handsome face, pulled off his hat and bent his head forward and flattened his hair to show the lump from his fall.

Instead of whatever else he should have said or done, Hero pointed at the tiny screen and said, “You want to see an American?”

And the Bolivian and the Polack and the Iranian, instead of laughing, or instead of ignoring Hero, stepped over to look. They cared about an American, even if Hero did not. Hero felt for his keys again, and despite himself he remembered the last summer he was a father—throwing fly balls in backyard evenings to a World Series announced by his youngest boy, announced in a voice still years from changing. On green, darkening grass he played catch wearing his older son’s, his wrong son’s, discarded mitt, with Alice calling them in because she knew he couldn’t see in the dark. She knew the balls that came back at him from their good boy were more than awkward; she knew they frightened him. She knew every weakness, and called him in, and he went in, furious and thirsty, leaving grass to the night.

The third baseman was nodding, neither patronizing the announcer nor taking himself as seriously as the announcer wanted. The third baseman smiled with a frank, open, blessedly regular smile. He smiled for an instant at the camera and at the men—no different than him, his smile seemed to say—at Hero, the barman, the Iranian, the Bolivian, and the Polack, all of whom looked back at that third baseman in silence.